Monarchs and Milkweed

The beauty and amazing migratory journey of the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) has captivated the public’s interest. But threats to its survival — including habitat loss, pesticide use and frequent roadside mowing — have created concern and a desire to help. Unfortunately, some of our efforts are causing more harm than good.

Scroll down to learn more.

Monarchs in Florida

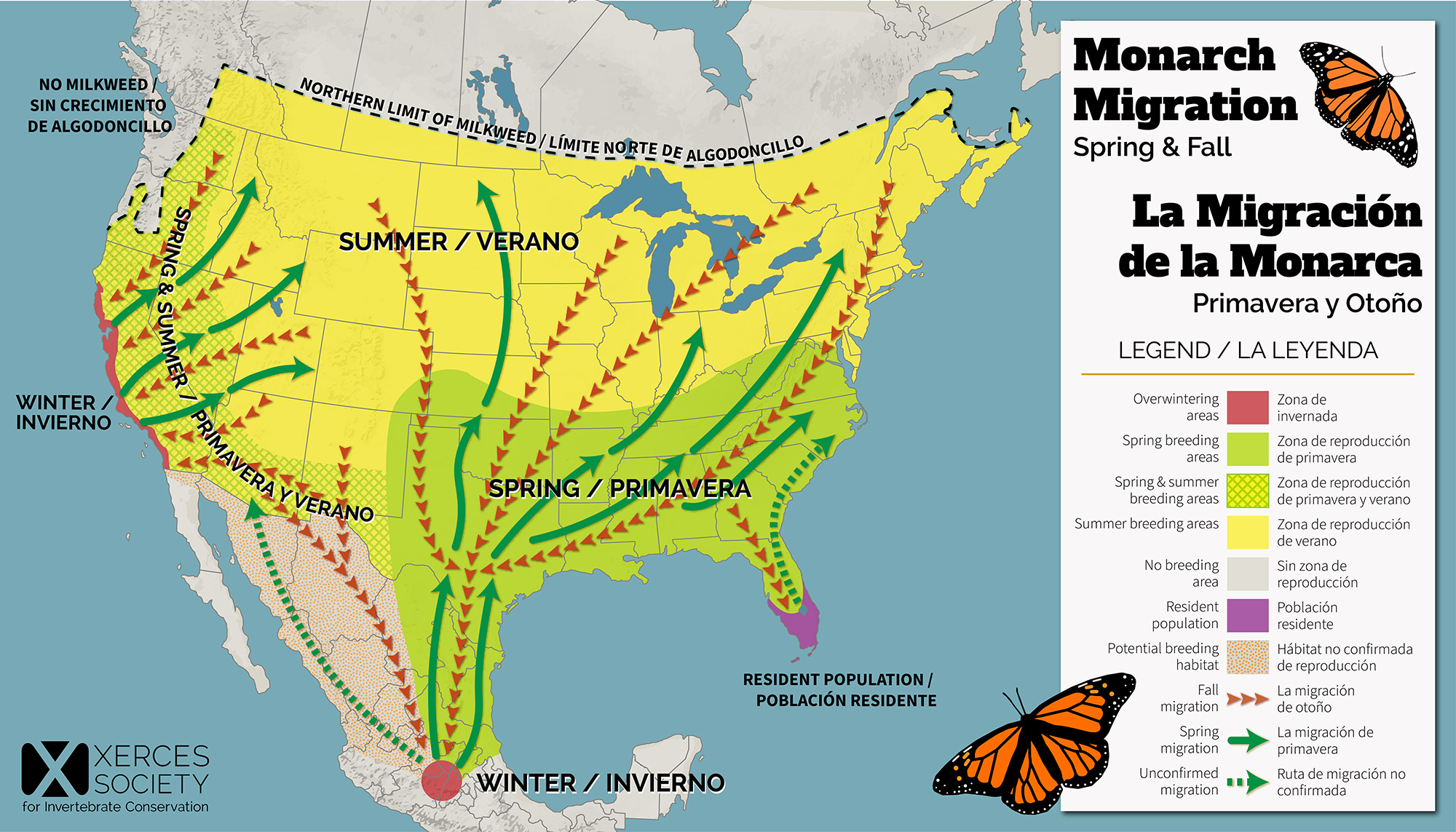

Historically, the Eastern migratory population of Monarchs moved through the Panhandle and North Florida on its annual journey. However, some of these Monarchs have deviated from their southwest route toward Mexico, and instead have traveled down Florida’s peninsula. While it is unclear where these butterflies ultimately end up, it is believed that some may migrate across the Gulf of Mexico, others may continue south into the Caribbean, and some may settle in South Florida, where a non-migratory population resides.

Beyond its significance in the migration route, North Florida also falls within the spring breeding range of Eastern migratory populations. In recent years, South Florida has witnessed a remarkable surge in its non-migratory population, primarily due to the widespread cultivation of non-native Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) and the practice of butterfly rearing. However, despite the good intentions behind these efforts, they have inadvertently resulted in harmful consequences.

Learn more about these complex issues in this webinar from Dr. Jaret Daniels:

Milkweed, Monarchs and OE in Florida: It’s Complicated

How you can help

In Florida, you can support Monarch butterflies by providing fall-blooming nectar plants for migrants, planting Florida’s native milkweeds for North Florida’s spring-breeding population and South Florida’s year-round population, and advocating for reduced mowing on roadsides.

Nectar for Monarchs

Plant these natives along with native milkweed to provide nectar for Monarchs:

- Blazing star (Liatris spp.)

- Snow squarestem (Melantherea nivea)

- Chaffhead (Carphephorus spp.)

- Climbing aster (Symphyotrichum carolinianum)

- Frostweed (Verbesina virginica)

- Flattop goldenrod (Euthamia caroliniana)

- Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

- Mistflower (Conoclinum coelestinum)

- Scorpiontail (Heliotropium angiospermum)

- Beggar’s tick (Bidens alba)

- Yellowtop (Flaveria linearis)

Why plant native?

Florida’s native plants have evolved here over thousands of years. They have symbiotic relationships with the wildlife and ecosystems around them, and have adapted to Florida’s unique climate, pests and soils. When the right plant is used in the right place in planted landscapes, they typically don’t need fertilizers or insecticides, or additional water once established.

Native milkweed

There are 21 milkweed species native to Florida. The three native species featured below are generally available at Florida native nurseries.

Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) is the most widely recognized native milkweed. Its showy clusters of bright reddish-orange flowers bloom late spring through fall. This native wildflower grows 12 to 15 inches high in a bushy form and has coarse lance- or oval-shaped leaves. Because it grows naturally in sandy habitats, it adapts well to dry landscapes.

Pink swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is found in moderate to moist sunny habitats, where it grows 2 to 4 feet tall. It blooms in summer with very showy light pink- to rose-colored flower clusters. Its fleshy linear leaves grow up to 6 inches.

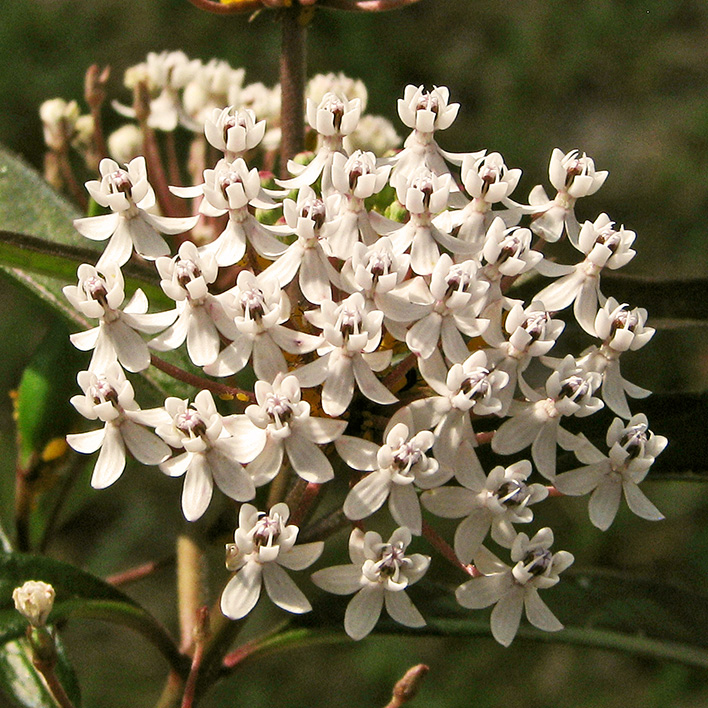

White swamp milkweed (Asclepias perennis) is a shorter bushy plant growing to about 2 feet. Summer flowerheads are small with white to light-pink flowers. Bright green leaves are lance-shaped. It prefers moist to wet soil conditions and can adapt to shady locations.

DID YOU KNOW?

Queen and Soldier butterflies also use native milkweeds as host plants for their caterpillars, and Pipevine, Spicebush and Eastern swallowtails rely on them for nectar. Many other butterflies and bees — including native sweat bees, leafcutter bees and yellow-faced bees — need milkweed’s pollen and nectar.

Pictured: Pipevine swallowtail on Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) by Mary Keim

Why aren’t native milkweed plants widely available?

Although they are robust in Florida’s natural habitats, native milkweeds can be difficult to propagate. Because they are a larval food source, butterfly larvae may devour milkweed foliage before the plants can be brought to market.

What we are doing

The Florida Wildflower Foundation, along with partners such as the Florida Museum of Natural History and Florida Association of Native Nurseries, is working to increase native milkweed production by supporting the sustainable collection of seeds from wild populations and the testing of propagation methods in order to develop and share best practices.

Where to purchase native milkweed plants

Act responsibly

Digging up wild native milkweed and collecting seed can reduce its ability to reproduce.

- Do not attempt to dig up wild native milkweed plants.

- Do not collect wild native milkweed seed unless you have permission from the landowner.

- If you have permission to harvest, take no more than 10 percent of the available seed.

How Tropical milkweed harms Monarchs

While it may sound like good news that South Florida’s resident Monarch population has grown, recent findings reveal a concerning trend: much of this population is unhealthy and exacerbating the spread of a detrimental parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE). The primary contributor to the prevalence of this parasite is Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica), which is native to Mexico and Central America. It is widely available at Florida’s mainstream nurseries and big box retail centers because it is easy to grow. However, the use of Tropical milkweed harms Monarchs in multiple ways.

Harm from parasites. Tropical milkweed has been linked to the higher transmission of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE), a protozoan parasite. When OE spores infect milkweed leaves, they can be carried on the bodies of adult butterflies, spreading the infection. Microscopic spores are spread to eggs, and infected larvae may not emerge from pupal stage or may emerge as very weak adults. Florida is now a hot spot for Monarchs heavily infected with OE. Learn more here. Find out if Monarchs in your area are infected and help contribute to ongoing research by participating in Project Monarch Health.

Harm from migration disruption. Tropical milkweed is evergreen and may bloom throughout winter, encouraging migratory Monarch populations to overwinter in Florida and continuously breed. This disruption of their natural life cycle makes them more susceptible to death from food shortages and freezing winter temperatures.

Overwintering Monarchs are also more susceptible to OE, which persists and accumulates in Tropical milkweed throughout the winter. (Native milkweeds lose their leaves and go dormant during the winter, which naturally reduces the presence of OE.)

Harm from insecticides. Commercially grown Tropical milkweed plants are sometimes treated with systemic insecticides to keep pests off of them, giving them a better appearance at retail nurseries. These insecticides can be very toxic to Monarch caterpillars that feed on the leaves, increasing mortality rates. Learn more in this study: Target and non-target effects of insecticide use during ornamental milkweed production, published in June 2024.

Commercially grown Tropical milkweed is also prone to heavy aphid infestations, which reduces the amount of eggs laid on plants and the vegetation available for feeding caterpillars.

Although not documented scientifically, the higher concentration of cardenolides toxin in Tropical milkweed may adversely affect Monarchs. The plant has also escaped into natural areas, which may further disrupt migration paths.