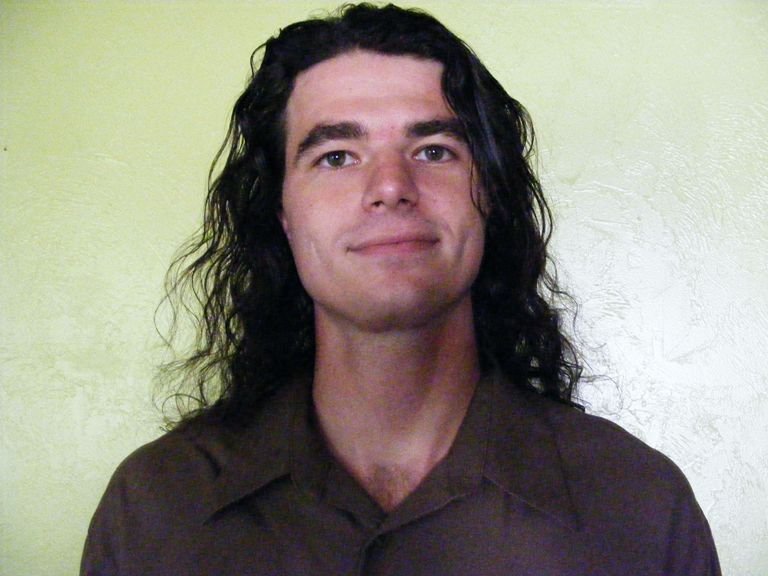

Member profile: Alan Franck

Dr. Alan Franck is curator of the University of South Florida Herbarium in Tampa, founded in 1958. It holds 285,000 specimens, and is the second largest collection in Florida. Alan has supported the Florida Wildflower Foundation through membership since 2011.

Join Alan Franck in supporting the Foundation by becoming a member or making a one-time donation to support our work.

Tell us a little about yourself.

I am from Ohio and moved to Florida in 2004. I started graduate school at USF in 2005.

Is there a moment you recall that first sparked your interest in the outdoors, specifically native flora?

West Ohio was very flat and replete with farms. In my small town, I experienced very little environmental education growing up. At around the age of 19, I started asking, “What is this? What is that? Where does it all come from?,” and realized I knew very little about much of anything. It was very exciting to explore and meet species I had never known before, appreciate them, and especially to encounter the quietude of wild plants where their individuality becomes so palpable.

How did you first get involved with the Florida Wildflower Foundation (FWF) and why do you stay involved?

I was asked to give a talk about the online Atlas of Florida Plants and give a workshop on specimen collecting for the 2011 Wildflower Symposium at Wekiwa Springs State Park. FWF has been very proactive in promoting and exalting the awareness of plants in Florida, and I greatly admire its educational outreach. FWF’s work complements the purpose and mission of the herbarium, which concerns taxonomy and plant naming. As I do my work there, I am hoping we are not just identifying plants for curiosity, but also promoting awareness of them, helping ultimately to educate others who will learn to care about them and promote their diversity and conservation.

Is there a favorite area in Florida where you like to botanize and enjoy wildflowers?

My favorite places to botanize are the nooks and crannies of vast wilderness areas – places where you’d like to think few have been.

The USF herbarium website states that 40 percent of the samples at the herbarium are from Florida. How were those samples collected and is the collection currently growing?

Of the 285,000 specimens from across the globe currently in the herbarium, about 40 percent were collected in Florida (including native and non-native species). The herbarium has more than 100,000 Florida specimens, collected by multitudes of individuals who have wandered through the Florida landscape. About one-third of our Florida specimens were collected by USF personnel. Several hundreds of others outside of USF also have contributed. Other herbaria, especially those in Florida, have given tens of thousands of specimens to us via mutual exchange, meaning we send them about an equal number of specimens as well. We recently were given the Florida Southern College herbarium, which has unique records from the 1920s to recent times. The oldest herbarium specimens at USF were collected by Ferdinand Rugel in the 1830s, although some European herbaria have specimens from Florida from the 18th century. On average, the USF collection grows by about 5,000 specimens per year, the majority of which are from Florida. Many USF personnel actively study and collect specimens, while several others donate specimens to us.

Click here to read Alan Franck’s 2016 publication, “Overview of the University of Florida’s Herbarium.”

As curator of the USF herbarium, can you share any current microbiology or molecular biology work being done on Florida wildflowers or native plants?

My molecular work is focusing on species relationships of endemic plants in the West Indies, which are also very deserving of research and conservation. Most of my research within Florida centers on traditional taxonomy by finding the best morphological characters by which to sort and identify species. Of course, multiple studies of this nature overlap between Florida and the West Indies. Along with a graduate student, I hope to begin paying some long overdue attention to Florida’s fleshy macrofungi, which generally benefit greatly from DNA-based studies.

What sparked your interest in the Harrisia (applecactus) species? Can you tell us about those plants and their distribution in Florida?

I was browsing for taxonomic problems of endangered and endemic plants in Florida, whittling down the list. I briefly considered Chionanthus (fringetree), but I have no idea what caused me to choose Harrisia in the end, as I had no particular fondness or hobby for succulents. It probably had something to do with their general neglect in being researched, which is often the case for bulky or spiny things. I originally focused only on the Florida species, but realized I couldn’t tackle that problem without the context of the surrounding species in the West Indies. Previously, three species of Harrisia were considered present in Florida. Based on my research, my opinion is that it is more useful to consider them as two species: H. aboriginum on the central-west coast and H. fragrans on the east coast and down through the Keys. The genus is remarkable for investing weeks into making a large, nocturnal flower that lasts only one night. Their flowers are taxonomically informative, and I had to grow many of the species in my yard just so I could catch a mature flower opening up.

You job sounds pretty full, but are there any new projects you are working on or dreaming of that include wildflowers?

I fantasize about being very familiar with local fungi, many of which are important mycorrhizal partners of plants, and I’d like to improve my knowledge of local bryophytes, the little plants. These are not wildflowers, but are certainly colleagues of them.

Do you have any ongoing landscape projects at your home or on the USF campus?

I dabble in cultivating edible or medicinal plants that do well in Florida, and occasionally share them with the USF Botanical Gardens. In particular, I search for subtropical/tropical perennials that are edible (especially their leaves) and don’t require a lot of attention.

What do you like most about native wildflowers? Do you have a favorite?

All of the mysterious ecological interactions that must take place among hundreds of species with just one individual plant — that is fascinating. I’ve always enjoyed encountering Passiflora incarnata (purple passionflower) with its artistically complex flowers, edible pulp, and the delightful teas made from the leaves.

Why should people care about wildflowers?

Diversity and resilience go hand in hand. The diversity of our species and the diversity of our environment (in our gut, on our skin, and around us) both generally increase our overall resilience (excepting that we do not favor those we consider pathogens, weeds, or threats to our resilience). Globally, humans depend on land plants (Embryophyta) for food, medicine, cosmetics, paper, textiles, construction materials, water and air quality, soil health, and beautification. Other species that humans depend on, such as pollinators and livestock, also themselves depend on land plants for food, habitat, and other resources. We could find many more uses from our local plants if we invested the time to research their potential, possibly even domesticate them, and educate others about their uses. It’s also nice to have a lovely oak tree to park under to keep my car cool during the day; it can shed all the leaves, pollen, and acorns it wants just to keep things cool.

What do you consider the greatest challenge facing Florida’s environment?

It’s the same as everywhere else: habitat destruction. Just consider how many species have lost more than 50 percent of their numbers in the past centuries, or how many have lost more than 90 percent of their population and continue to erode today. Surely more than a few. Even though many species may still persist on the planet, the loss of diversity within a species is concerning. Of course, climate and rising sea level is also something to be cognizant of. There are also some non-native plants that seem especially pernicious to some habitats, and FLEPPC does a fine job of pointing those out. But on the whole, finding a species non-native to a region is not inherently wrong; I like non-native plants just as much as native ones. Where else would I get my food and herbs? Only a few (but a significant few) out of thousands and thousands of non-native species become problematic in a region. My concern is for a healthy environment that retains the diversity of its native species, and not so much whether a species that arrived in Florida after Ponce de Leon (non-native) is also present. Mainly, it’s wanton environmental destruction that bothers me.

Do you have any suggestions to help spread the word about wildflower appreciation or conservation?

Other than vigilant communications with our world, I think we most need education and reminders that everything comes from the environment, whether it’s from rock or mineral, water, oil, or gas, or from living organisms. It all comes from the environment, an environment that has shaped and formed itself over many, many, many, many years.