Drawn to nature

Drawn to nature

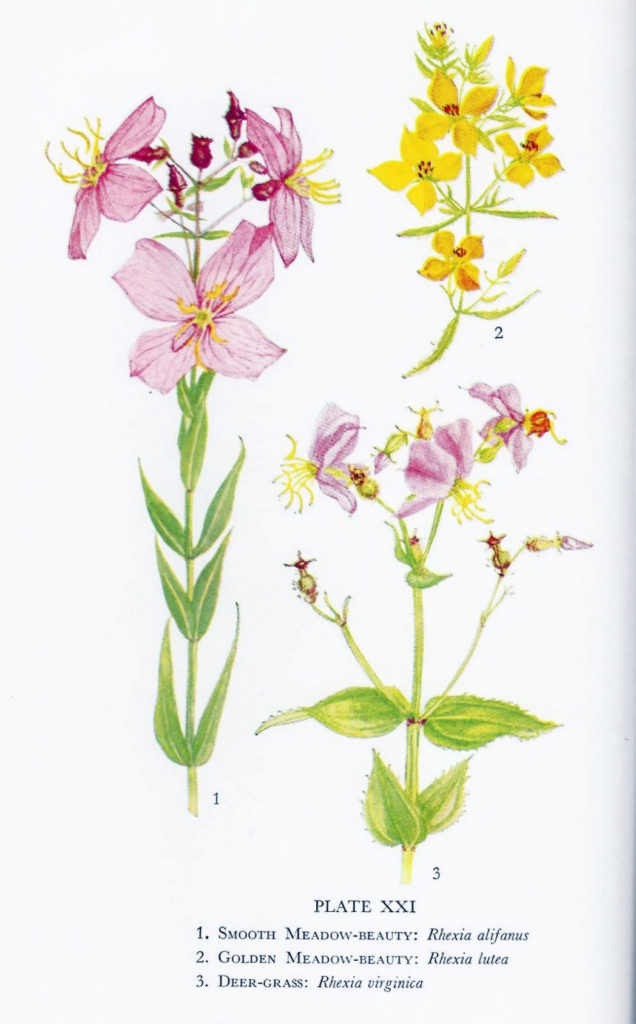

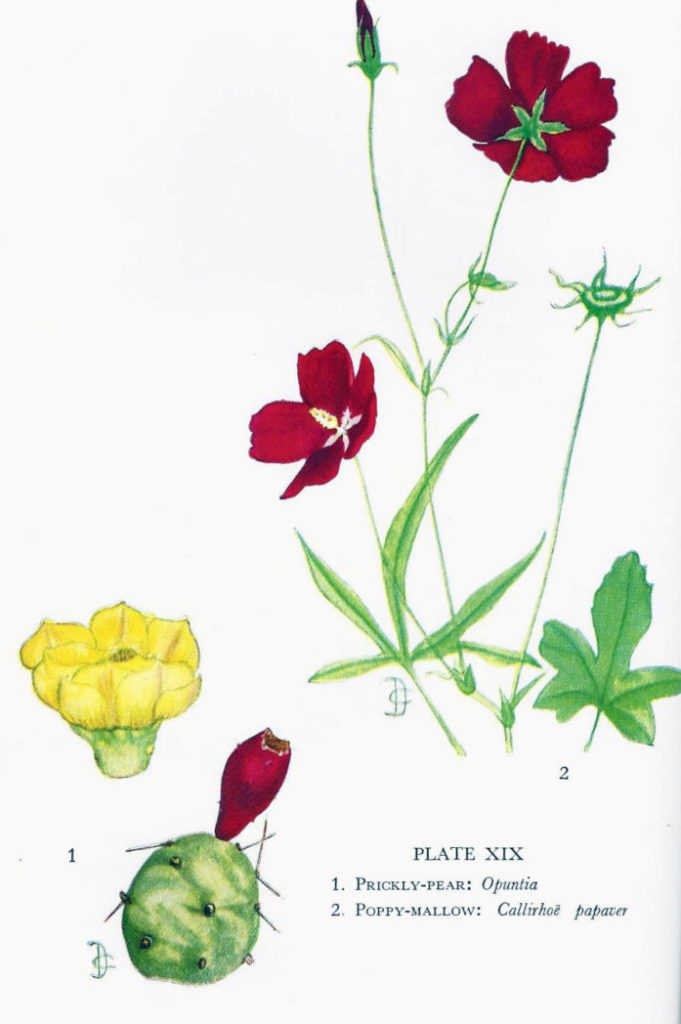

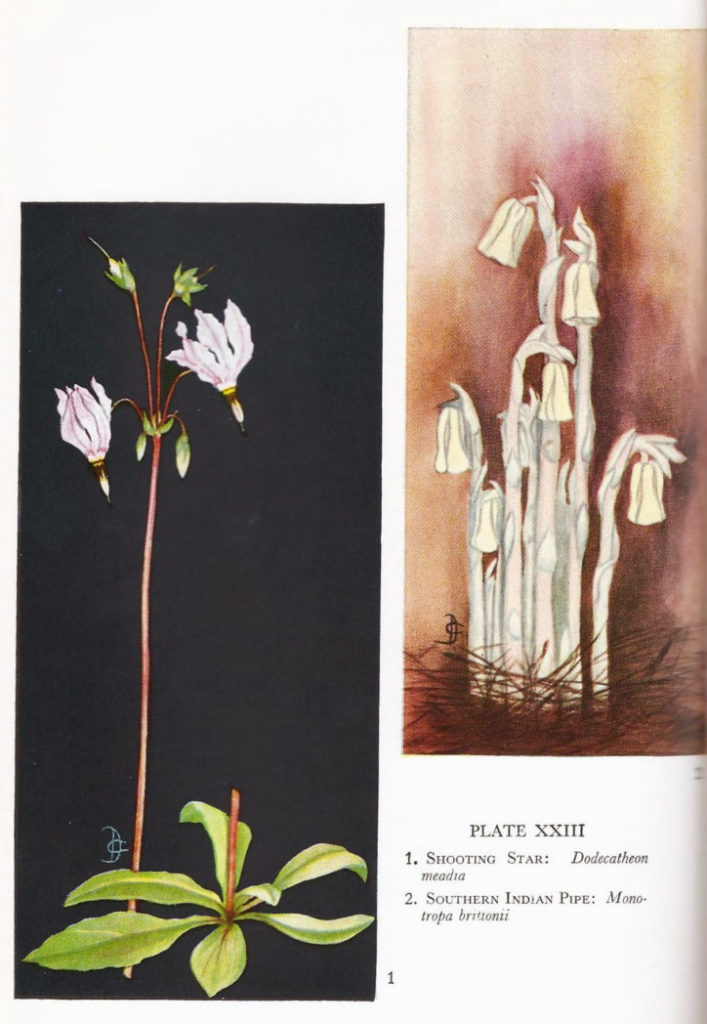

Caroline Dorman’s illustrations in Flowers Native to the Deep South exemplify the artistic grace of her subjects.

Botanical art treasures stand test of time

by Claudia Larsen

When it’s time to identify a wildflower, most of us head for our favorite field guide and look through beautiful close-up photographs until we find our subject. Some versions are even color-coded to aid the process. I must own all the popular Florida books by now, but alongside those on my bookshelf are also several special volumes I have collected just for their beautiful hand-drawn reproductions of wildflowers.

My favorite is Caroline Dorman’s Flowers Native to the Deep South (1958; Claitor’s Bookstore, Baton Rouge, LA). In the foreword, the author writes, “It is hoped that this book will help arouse renewed interest in the preservation of our rapidly vanishing wild flowers [sic]. From too frequent picking, misdirected efforts to move them to gardens, forest fires and onslaughts of rabbits and insects, some species are becoming very rare.” Doesn’t her message sound familiar even after all these years? She states that all but two illustrations were drawn from a living flower (some provided by renowned botanist Dr. J.K. Small). These include 33 color plates and 102 black and white drawings. The most stunning flowers, including the white swamplily (Crinum americanum) and the fringed orchid (Habenaria ciliaris), are set against black backgrounds that contrast beautifully and create a dramatic effect.

Flowers have been the inspiration for many artists throughout history. Early books of botanical illustrations were popularized by the infatuation with the language of flowers in which certain flowers symbolized sentiments of hope, friendship, love and, of course, secret love. In the 17th and 18th centuries “florilegiums,” or flower books, became popular. They held accurate drawings of flower parts, stems and roots. Early printing processes included original illustrations transferred to stone or copper for printing. After the design was transferred to paper, it was hand-colored by artists.

As gardening and plant-collecting increased in popularity, so did the ownership of herbarium albums, botanical magazines and books. Privileged women hired art teachers and used instructional drawing books to aid their favorite pastime of drawing and painting with watercolors. Examples of these include Easy Introduction to Drawing Flowers According to Nature (James Sowerby; 1788) and Sketches of Flowers from Nature (Mary Lawrence; 1801). Many of these albums, which included poetry and gardening advice, were never published. Today they are anonymous works of art stored in various libraries and private collections.

Interest in nature continued to flourish in the 19th and 20th centuries, and illustrations depicted collections of regional plants, birds and animals. In 1850, Susan Fenimore Cooper’s artwork in her Rural Hours by a Lady reflected the natural world in upstate New York. Her contemporary, Mrs. Clarissa W. Munger Badger, published Wildflowers of America in 1859.

I can only imagine the beautiful landscapes experienced by Emma Homan Thayer when she created Wildflowers of Colorado in 1885, followed by Wildflowers of the Pacific Coast in 1887. She states in her book, “In the places most difficult to access, I found the most beautiful flowers. It would seem as if they wished to hide the delicate members of their family from the rude gaze of the world, sheltered in some nook of the rocks, like a miniature conservatory tenderly cared for by the fairies of the mountains.”

Women who were paid for their illustrations were often criticized and generally unrecognized for their contributions to important botanical manuscripts, but botanical illustration encouraged personal observation and self-education in the new science of botany, as well as other sciences.

Today, illustrators are prominent in many fields of science and engineering. Government publications also fortified illustrated collections of wildflowers and native plants in manuals such as the annual Yearbook for the US Department of Agriculture.

More recent illustrated manuals on wildflowers are both artistic and instructional. The Illustrated Plants of Florida and the Coastal Plain, (Dr. David Hall; 1993) boasts 1,200 illustrations by Edward H. Stehman from specimens that were collected between 1966 through 1989. Black and white drawings were chosen to represent the plants “since photographs frequently do not show accurate details.”

For exquisitely detailed and accurate botanical line drawings, there are few better than Wendy B. Zomlefer’s collection in Flowering Plants of Florida – A Guide to Common Families (1989). Wendy’s taxonomic renditions include amazing cross-sections of flower heads and seed structures that can be used to distinguish plant species. She makes great use of the stippling technique to create a three-dimensional affect.

Another regional favorite that includes wildflowers is Gil Nelson’s Florida’s Best Native Landscape Plants (2003). Each species represented has color photos, and many also include meticulously beautiful watercolor portraits by illustrators Jean Hancock and Susan Trammell, which gives this book a unique artistic touch.

If you’re looking for inspiration for your own drawings, check out Southern Wildflowers by Georgia magazine garden editor Laura Martin (1989). She describes 70 common wildflowers and gives cultivation advice and historical backgrounds. Full-color illustrations by Mauro Magellan accompany the text. The drawings are quite ethereal (I was startled to read the artist is also the drummer for the rock group Georgia Satellites.)

References

- Women of Flowers – A Tribute to Victorian Women Illustrators by Jack Kramer

Claudia Larsen owns and operates Micanopy Wildflowers, a native-plant nursery in Micanopy, Fla.